Who are you calling a turkey?

Thanksgiving means many things to many people, but the core of the holiday is a big meal shared with family and friends. Traditionally, of course, the meal is centered around a roasted turkey. Domestic turkeys were derived from our native wild turkey (Meleagris gallopavo), and are considered to be the same species. Turkeys apparently were originally domesticated in southern Mexico in the 1500s by the conquering Spanish forces, although Indigenous cultures in both North and Central America have been eating both species of turkey for millennia.

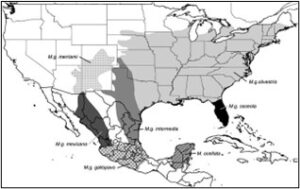

Indigenous cultures in the southwest of North America also independently domesticated turkeys, but those bloodlines did not persist into modern domestic populations. The subspecies M. gallopavo gallopavo, the form domesticated by the Spanish in southern Mexico, is now extinct but native wild turkeys persist in more northerly regions of Mexico. A second species of turkey, the spectacular ocellated turkey (Meleagris ocellata) is native to Central America. So both species have historically been heavily hunted for food by various cultures and are reliant on carefully implemented and enforced conservation laws as well as protected areas.

Hunting has not been the only conservation challenge to the wild turkey in North America. Historically, it ranged across areas now represented by 39 different US states, plus adjacent regions of Canada and Mexico. By the 1800s, however, most of the forests in the eastern third of the United States had been cleared or badly degraded. American chestnut trees were a conspicuous dominant species in those forests, and the introduced chestnut-blight fungus, compounded by deforestation, eliminated this tree that served as an important food source for turkeys, passenger pigeons, and many other species. By 1813 Connecticut had no turkeys, and Vermont also by 1842. By 1920, turkeys were gone from 18 states, mostly in New England and the upper Midwest region. Elsewhere, turkeys simply had become very rare birds.

Hunting was outlawed and by the middle of 1900s, state and federal agencies were actively trying to restore turkey populations in the U.S. as the forests slowly recovered. Captive breeding efforts were not very successful, apparently, because the “pen-raised” hatchlings were not properly reared by the mother and did not fare well upon release. Disease outbreaks in the captive turkeys also affected recovery efforts. Eventually, the captive programs were cancelled. Capturing wild birds from the few, and very remote, persisting wild populations and relocating them to historical areas of their range was a much more successful strategy. By the 1970s, some states once again allowed hunting of the recovering populations under carefully controlled guidelines and limits.

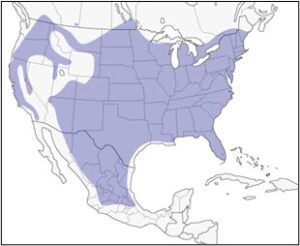

The historical and current ranges of wild turkey are shown left (borrowed from Thornton, 2016, and the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology). Websites about wild turkeys glowingly describe the recovery program as a huge success and point out proudly that the species now occurs in 49 states, including Hawaii, but excluding Alaska. The current distribution is shown here (from the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology). Recall that originally their range included 39 states, certainly not including Hawaii, but also not including the westernmost states. This difference is because, in their zeal to recover wild turkey populations and develop sport-hunting for them, the state and federal agencies translocated birds outside of their historical range. This was a highly questionable approach that has resulted in robust wild populations in places like California, where they never occurred naturally. Foraging turkeys are like vacuum cleaners on the forest floor, devouring all forms of fruits, seeds, and small animals. There was no ecologically similar species in these newly populated areas, so native plants and animals palatable to turkeys are now facing a unique predator in their evolutionary history. As conservationists, we often talk about the negative impacts of non-native invasive species, such as Burmese pythons in the Everglades ecosystem. So, I find it quite ironic that we celebrate our successful establishment of these birds in these non-historical ranges. In other words, many are celebrating this now-established species that qualifies as an invasive as a conservation success. Perhaps too much success is not always a good thing?

While we do not have wild turkeys among the Zoo’s populations, there is a population of them in the Grant Park neighborhood. I have seen them crossing Cherokee Ave SE in broad daylight, and I well recall a group settling in our Hoofstock yard a number of years ago. They spent about an hour just meandering and foraging among the giraffes and zebras. So, keep your eyes open!

Joe Mendelson, PhD

Director of Research

References:

Thornton, E.K., 2016. Introduction to the special issue-Turkey husbandry and domestication: Recent scientific advances. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 10, pp.514-519.

Connect With Your Wild Side #onlyzooatl